Without ringing my bike bell too loudly, the fourth edition of my Watts Happening Ride that took place May 8, 2010, was the best ever and the largest endeavored. It involved my most extensive level of internet-combing research for eight of the nine places we visited (I left Watts Towers to the expert tour guides on hand).

I was immensely pleased to share what I discovered with the nearly 20 cyclists who came along for the ride and tolerated my inability to edit (as well as my ability to get choked up at Eula Love’s home).

So out of pride and for posterity and for anyone interested in taking a virtual tour from the comfort of their internet access device, I present all that information in sequence:

- Nobel Peace Prize Winner Ralph Bunche’s childhood home

- The location of the 1969 Shootout between LAPD and Black Panthers at Black Panther Part headquarters

- The Dunbar Hotel and the Central Avenue Jazz Corridor

- The site of the 1974 shootout between SLA members and the LAPD

- The Watts Towers of Simon Rodia

- The site of the arrest that set off the 1965 Watts Riots

- The home of Eula Love

- Flashpoint of the 1992 LA Riots

- Site of Wrigley Field

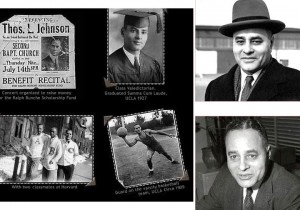

Stop No. 1: Childhood Home of Nobel Peace Prize Winner Ralph Bunche – 1220 E. 40th Place

Ralph Johnson Bunche was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1903. His father, Fred Bunche, was a barber in a shop having a clientele of whites only; his mother, Olive (Johnson) Bunche, was an amateur musician; his grandmother, Nana Johnson, who lived with the family, had been born into slavery. When Bunche was 13-14, the family moved to Albuquerque in the hope that the poor health of his parents would improve in the dry climate. His father soon left in search of work and never returned. Following the death of his mother and the suicide of his uncle Charles, his grandmother took Ralph and his two sisters to this house on 40th Place several blocks east of Central Avenue (pictured) where he lived for about 10 years. Here Ralph contributed to the family’s hard pressed finances by selling newspapers, serving as house boy for a movie actor, working for a carpet-laying firm, and doing what odd jobs he could find.

Ralph Johnson Bunche was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1903. His father, Fred Bunche, was a barber in a shop having a clientele of whites only; his mother, Olive (Johnson) Bunche, was an amateur musician; his grandmother, Nana Johnson, who lived with the family, had been born into slavery. When Bunche was 13-14, the family moved to Albuquerque in the hope that the poor health of his parents would improve in the dry climate. His father soon left in search of work and never returned. Following the death of his mother and the suicide of his uncle Charles, his grandmother took Ralph and his two sisters to this house on 40th Place several blocks east of Central Avenue (pictured) where he lived for about 10 years. Here Ralph contributed to the family’s hard pressed finances by selling newspapers, serving as house boy for a movie actor, working for a carpet-laying firm, and doing what odd jobs he could find.

His intellectual brilliance appeared early. He won a prize in history and another in English upon completion of his elementary school work and was the valedictorian of his graduating class at Jefferson High School in Los Angeles, where he had been a debater and all-around athlete who competed in football, basketball, baseball, and track. At the University of California at Los Angeles he supported himself with an athletic scholarship, which paid for his collegiate expenses, and with a janitorial job, which paid for his personal expenses. He played varsity basketball on championship teams, was active in debate and campus journalism, and was graduated in 1927, summa cum laude, valedictorian of his class, with a major in international relations.

With a scholarship granted by Harvard University and a fund of a thousand dollars raised by the black community of Los Angeles, Bunche began his graduate studies in political science. He completed his master’s degree in 1928 and for the next six years alternated between teaching at Howard University and working toward the doctorate at Harvard, awarded in 1934.

With a scholarship granted by Harvard University and a fund of a thousand dollars raised by the black community of Los Angeles, Bunche began his graduate studies in political science. He completed his master’s degree in 1928 and for the next six years alternated between teaching at Howard University and working toward the doctorate at Harvard, awarded in 1934.

In 1936 Bunche wrote a book titled A World View of Race. In it Bunche wrote: “And so class will some day supplant race in world affairs. Race war will then be merely a side-show to the gigantic class war which will be waged in the big tent we call the world.” In 1936-40 Bunche served as contributing editor of the journal Science and Society: A Marxian Quarterly.

Bunche spent time during World War II in the Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor of the CIA) as senior social analyst on Colonial Affairs before joining the State Department where in 1943 he was appointed Associate Chief of the division of Dependent Area Affairs under Alger Hiss. IN 1945 he participated in the preliminary planning for the United Nations at the San Francisco Conference.

In 1946, the UN Secretary General borrowed Bunche from his job with the US State Department  and placed him in charge of the Dept of Trusteeship of the UN to handle problems of the world’s peoples who had not yet attained self-government.

Beginning in 1947 Bunch went to work on the most important assignment of his career – the confrontation between Arabs and Jews in Palestine, where he was ultimately charged with carrying out the partition approved by the UN General Assembly. In 1948 when fighting between Arabs and Israelis was particularly severe, Bunche was appointed chief aide to mediator Count Benadotte who was assassinated four months later by a Jewish extremist group that considered him anti-Zionist. One member of that group who was alleged to have authorized the murder was Yitshak Shamir. Shamir later became Israel’s prime minister from 1983-84 and again from 1986-1992.

Bunche was immediately named acting UN mediator on Palestine. And after eleven months of virtually ceaseless negotiating, Bunche obtained signatures on armistice agreements between Israel and the Arab States.

Bunche returned home to a hero’s welcome. New York gave him a ticker tape parade up Broadway; Los Angeles declared a Ralph Bunche Day. He was besieged with requests to lecture, was awarded the Spingarn Prize by the NAACP in 1949, was given over thirty honorary degrees in the next three years, and the Nobel Peace Prize for 1950.

- 1963- He received the ‘Medal of Freedom’ from President John F. Kennedy.

- 1965- He took part in Civil Rights march led by Martin Luther King Jr in Montgomery, Alabama.

- 1968- He became the undersecretary-general of the UN.

- 1971 – in New York City.

- 1978 – The home is named LA Historic-Cultural Monument No. 159

- 2002 – Home restored, becomes the Dr. Ralph J. Bunche Peace & Heritage Center

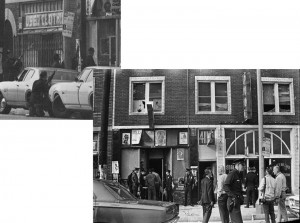

Stop No. 2: 1969 Black Panther/LAPD Shootout – 4115 S. Central Avenue

The Black Panther Party was an African-American revolutionary leftwing organization working for the self-defense for black people.

From the beginning the Black Panther Party’s focus on militancy came with a reputation for violence. They employed a California law which permitted carrying a loaded rifle or shotgun as long as it was publicly displayed and pointed at no one.[38] Carrying weapons openly and making threats against police officers, for example, chants like “The Revolution has co-ome, it’s time to pick up the gu-un. Off the pigs!,” helped create the Panthers’ reputation as a violent organization.

The Southern California branch of the Black Panther Party was founded by Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter. Carter was a leader in the Slausons gang and its spinoff the Slauson Renegades. Carter spent four years in prison and became a Muslim there. He formed and headed the Southern California chapter in early 1968. Carter and Deputy Minister John Huggins were killed in Campbell Hall on the UCLA campus, in a January 1969 gun battle with members of the Black Nationalist Group US Organization stemming from a dispute over who would control UCLA’s black studies program.

In April 1969, hundreds of Panthers were meeting on the second floor of this building when a corresponding amount of LAPD officers from the Newton Street Division surrounded it. The chapter’s leader at the time, Geronimo Pratt, turned off the lights, arming and organizing the Panthers to defend themselves. Panthers Joan Kelley and Elaine Brown contacted the news media, which some say is why the LAPD ultimately withdrew. In my personal opinion I don’t thing the LAPD gave a lick about the media or how it might portray the department. I think they realized they were outgunned and rather than engage in a bloodbath retreated to fight another day when the numbers were more in their favor.

That day came on December 8, 1969, when the LAPD deployed its brand new militarized police units, known as SWAT teams in their first engagement, a warrant, a battering ram, helicopters, a tank, trucks, dynamite, and 400 police officers to raid three Los Angeles-area Black Panther Party Facilities facilities including the headquarters at 4115 S. Central Avenue.

That day came on December 8, 1969, when the LAPD deployed its brand new militarized police units, known as SWAT teams in their first engagement, a warrant, a battering ram, helicopters, a tank, trucks, dynamite, and 400 police officers to raid three Los Angeles-area Black Panther Party Facilities facilities including the headquarters at 4115 S. Central Avenue.

The Panthers there under Geronimo Pratt’s leadership, barricaded themselves inside and stood their ground. Only after exchanging fire with the police for five hours,which resulted in six Panthers and three officers being wounded, did they surrender,

Participant Melvin Cotton Smith, security officer for the L.A. branch, was later identified by former government agent Louis Tackwood as a police informant. Tackwood, too, was a government infiltrator of the Los Angeles BPP. Smith provided the LAPD and FBI with detailed blueprints of party facilities before the raid. The LAPD’s warrant was reportedly obtained on the basis of false information provided by the FBI regarding stolen military weapons.

The day after the raid, Angela Davis and others set up a vigil outside this building until LAPD officers advanced on them and drove the assembly away.

In 41st & Central, a recently released documentary offering and unblinking look at the Los Angeles Black Panther Party, former member Wayne Pharr is quoted as saying of the shootout:

“That was the only time as a black man in America that I ever felt free.â€

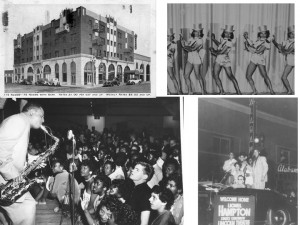

Stop No. 3: The Dunbar Hotel &Â The Central Avenue Jazz Corridor – 4225 S. Central Avenue

Central Avenue from downtown Los Angeles to Watts was a thriving cultural center much like Harlem was to New York. In fact, its creation was due to segregation and land-use prohibitions. African Americans moving to California wound up in these surrounding communities because of covenants that restricted where they could live and run businesses. Thus Central Avenue ascended to become the social and cultural center populated with a variety of black-owned clubs. During its 35-year heyday Hollywood stars such as Humphrey Bogart rubbed elbows with local butchers, bakers and candlestick makers backed by a never-more-robust jazz soundtrack.

It wasn’t until after World War II that deed restrictions ended. That, coupled with City Hall and law enforcement harassment, effectively brought an end to this cultural cauldron scattering the African-American community throughout the greater LA area.

But at the center of it all was the historic Dunbar Hotel. Opened by Jamaican-born John Alexander Somerville in 1928 as the Hotel Somerville, it hosted the first national convention of the NAACP to be held in the western United States.

More than 5,000 people stopped by the four-story hotel opening day. Visitors were met with a ground floor that contained stores, a barbershop, a beauty parlor, and a flower shop. The Somerville’s dining room could hold 100 diners and featured a balcony for an orchestra.

Of it civil rights activist WEB Du Bois wrote:

“It was a a jewel done with loving hands… It was full of sunshine and low voices and the sound of human laughter and running water. The hotel Somerville was an extraordinary surprise to people fed on ugliness – ugly schools, ugly churches, ugly streets, ugly insults. We were prepared for – well, something that didn’t leak, that was hastily clean and too new for vermin. And we entered a beautiful new inn with a soul… Funny that a hotel so impressed – but it was so unexpected, so startling, so beautiful.â€

The stock market crash of 1929, brought about a change in ownership and a new name after the African-American poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar.

The Hotel Dunbar positioned itself as a “first-class establishment†and it was soon considered top notch with travelers for its attentive service and luxurious accommodations. Many early Black movie stars like the Mills Brothers, would come to LA to do a film, find that they were not welcome to spend the night in Hollywood, but were embraced and pampered at the Dunbar. Because of this, the community soon focused on the Dunbar as the place to spot celebrities of the day. Among them: Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, Langston Hughes, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat Cole, Cab Calloway, Lionel Hampton, Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, Count Basie, Louie Armstrong, Jellyroll Morton, Charlie Mingus, Miles Davis, or Charlie Parker when they came here to stay perform. Duke Ellington maintained a year-round suite in the Dunbar.

The Hotel Dunbar positioned itself as a “first-class establishment†and it was soon considered top notch with travelers for its attentive service and luxurious accommodations. Many early Black movie stars like the Mills Brothers, would come to LA to do a film, find that they were not welcome to spend the night in Hollywood, but were embraced and pampered at the Dunbar. Because of this, the community soon focused on the Dunbar as the place to spot celebrities of the day. Among them: Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, Langston Hughes, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat Cole, Cab Calloway, Lionel Hampton, Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, Count Basie, Louie Armstrong, Jellyroll Morton, Charlie Mingus, Miles Davis, or Charlie Parker when they came here to stay perform. Duke Ellington maintained a year-round suite in the Dunbar.

Other noteworthy people who stayed at the Dunbar include, Joe Louis, Ray Charles and Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. Former heavyweight champion Jack Johnson also ran a nightclub at the Dunbar in the 1930s.

Surrounding the Dunbar were numerous Jazz clubs, their neon signs signs lighting up the night. There was the Club Alabam (with its full chorus line just like the famous Cotton Club in New York), the Last Word, Dynamite Jackson’s, The Apex, The Hole in the Wall, Jack’s Basket, The DownBeat, The Memo Club, Ivie’s Chicken Shack, and many more.

In 1974, the Dunbar became Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 131. But The Dunbar is no longer a privately owned hotel but instead operates as low-income housing. The 15th Annual Central Avenue Jazz Festival is scheduled to take place July 24-25.

One of the best books ever on the subject of Jazz in Los Angeles is called Central Avenue Sounds.

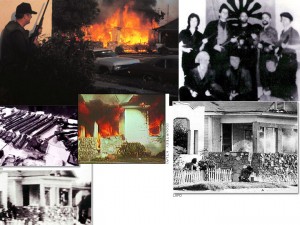

Stop No. 4: 1974 SLA/LAPD Shootout – 1466 E. 54th St

What was the Symbionese Liberation Army? The SLA was an American self-styled leftwing urban militant group active between 1973 and 1975 that considered itself a revolutionary vanguard army. The group committed bank robberies, two murders and other acts of violence.

In his manifesto, SLA founder Donald DeFreeze wrote “The name ‘symbionese’ is taken from the word ‘symbiosis’ and we define its meaning as a body of dissimilar bodies and organisms living in deep and loving harmony and partnership in the best interest of all within the body.”

On November 6, 1973, in Oakland , Calif, they targeted a body they felt wasn’t living in the kind of harmony and partnership they demanded: School Superintendent Marcus Foster, who was assassinated by two members at an Oakland school board meeting. The hollow-point bullets used to kill Foster had been packed with cyanide. The SLA had condemned Foster for his plan to introduce identification cards into Oakland schools. The SLA called him “fascist.” Ironically, Foster had originally opposed the use of identification cards in his schools, and his plan was a watered-down version of other similar proposals. Foster, an African-American, was popular on the Left and in the black community, so his assassination did little to endear the SLA to them.

That murder put the SLA on a lot of most wanted lists, but what made them internationally notorious was the kidnapping of media heiress Patty Hearst, abducting the 19-year-old from her Berkeley, California home on February 4, 1974. National interest grew into worldwide fascination when Hearst denounced her parents and announced she had joined the SLA. Though they figured with Hearst onboard there’d be a rush of new recruits wanting to join them up in the Bay Area, that turned out not to be the case so the SLA opted to relocate to this area of South Los Angeles where DeFreeze had grown up and reportedly had friends they might enlist.

That didn’t pan out either. And it was after a botched-shoplifting at Mel’s Sporting Goods on May 16 in Inglewood, (in which Hearst shot up a storefront sign), that ultimately led more than 400 LAPD, CHP, FBI and LAFD personnel to surround the bungalow that used to stand at 1466 E. 54th Street where at 5:45 p.m. on May 17, 1974, SWAT Team 1 Leader announced via bullhorn:

“Occupants of 1466 E. 54th St., this is the Los Angeles Police Department speaking. Come out with your hands up!”

A small child walks out, along with an older man. The man claims no one else is in the house, though the child states that several people were in the house with guns and ammunition belts.

At 5:53 p.m. after several failed attempts to get anyone else to leave the house, a member of SWAT fires two tear gas projectiles through a window. As soon as the second gas projectile disperses, heavy bursts of gunfire come from inside the front and rear of the house. Numerous bullets strike the buildings and trees across from and to the rear of the SLA hideout. The gun battle continues for almost an hour until smoke is seen coming from the house. A bullhorn broadcast pleads, “Come on out! The house is on fire! You will not be harmed.” There is no response while the house becomes fully engulfed in flames, At 6:50 p.m. the SWAT teams start receiving automatic weapons fire from air vents in the foundation of the house. Member Nancy Ling Perry, wearing military fatigues with a hunting knife attached to a web belt, comes out of a crawl hole. A second female, Camilla Hall, starts to emerge from the crawl hole, firing a pistol toward members of SWAT. At this time, automatic weapons fire is still coming from the crawl hole behind Hall. Law enforcement officers fire in the direction of Hall and she falls to the ground where she’s dragged back inside, out of view. Perry falls approximately ten feet from the crawl hole.

At 5:53 p.m. after several failed attempts to get anyone else to leave the house, a member of SWAT fires two tear gas projectiles through a window. As soon as the second gas projectile disperses, heavy bursts of gunfire come from inside the front and rear of the house. Numerous bullets strike the buildings and trees across from and to the rear of the SLA hideout. The gun battle continues for almost an hour until smoke is seen coming from the house. A bullhorn broadcast pleads, “Come on out! The house is on fire! You will not be harmed.” There is no response while the house becomes fully engulfed in flames, At 6:50 p.m. the SWAT teams start receiving automatic weapons fire from air vents in the foundation of the house. Member Nancy Ling Perry, wearing military fatigues with a hunting knife attached to a web belt, comes out of a crawl hole. A second female, Camilla Hall, starts to emerge from the crawl hole, firing a pistol toward members of SWAT. At this time, automatic weapons fire is still coming from the crawl hole behind Hall. Law enforcement officers fire in the direction of Hall and she falls to the ground where she’s dragged back inside, out of view. Perry falls approximately ten feet from the crawl hole.

At 6:59, hostile fire ceases, but unexpended ammunition stockpiled inside continues to explode in the fire, which the fire department begins extinguishing at the location and at the three adjacent residences. All fires are out by 7:30 p.m.

It is estimated some 9,000 rounds were exchanged during the battle, which was broadcast live via local stations and picked-up nationally. In all six SLA members died. Three were shot by police, two succumbed to smoke inhalation and burns. DeFreeze shot himself in the head, according to the coroner. While it was feared that Heast’s charred body would be found among those burned beyond recognition, in fact, she had watched the whole thing play out on TV from the safety of an Anaheim motel room.

Hearst was captured in 1975. Sentenced to seven years in prison, she served 21 months when her sentence was commuted by President Jimmy Carter. Eventually she was pardoned by President Bill Clinton.

Stop No. 5: Watts Towers of Simon Rodia, 1765 E. 107th Street

No notes compiled/recited by me for this landmark since it was open for tours ($7, cash only) given by personnel faaaaaaar better versed in its history, details and significance. From its webpage on the California State Parks site:

No notes compiled/recited by me for this landmark since it was open for tours ($7, cash only) given by personnel faaaaaaar better versed in its history, details and significance. From its webpage on the California State Parks site:

The Watts Towers are a complex set of 17 separate sculptural pieces built on a residential lot in the community of Watts. Two of the towers rise to a height of nearly 100 feet. The sculptures are constructed from steel pipes and rods, wrapped with wire mesh, coated with mortar, and embedded with pieces of porcelain, tile and glass. Using simple hand tools and cast off materials (broken glass, sea shells, generic pottery and ceramic tile) Italian immigrant, Simon Rodia spent 30 years (1921 to 1955) building a tribute to his adopted country and a monument to the spirit of individuals who make their dreams tangible.

The Watts Towers are one of only nine works of folk art listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The site is one of only four US National Historic Landmarks in the city of Los Angeles. The site is now a unit of California State Parks and managed by the Los Angeles City Cultural Affairs Department.

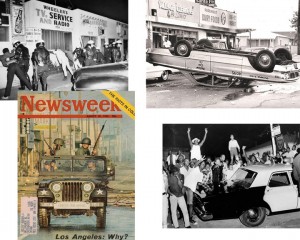

Stop No. 6: 1965 Watts Riots Flashpoint – 116th Street & Avalon Boulevard

On August 11, 1965, California Highway Patrolman Lee W. Minikus, was riding his motorcycle along 122nd street, just south of the Los Angeles City boundary, when a passing Negro motorist told him he had just seen a car that was being driven recklessly. Minikus gave chase and pulled the car over at 116th and Avalon. It was 7 p.m.

The driver was Marquette Frye, a 21-year-old African-American. His older brother, Ronald, 22, was a passenger. Minikus asked Marquette to get out and take the standard Highway Patrol sobriety test. Frye failed the test, and at 7:05 p.m., Minikus told him he was under arrest. He radioed for his motorcycle partner, for a car to take Marquette to jail, and a tow truck to take the car away.

The arrest occured w two blocks from the Frye home, in an area of two-story apartment buildings and numerous single-family residences. Because it was a very warm summer evening, many of residents were outside.

Ronald Frye, having been told he could not take possession of the car when Marquette was taken to jail, went to get his mother so that she could claim the car. They returned to the scene about 7:15 p.m. as the second motorcycle patrolman, the patrol car, and tow truck arrived. The original small group of curious spectators had grown to an estimated crowd of 300. Mrs. Frye approached Marquette and scolded him for drinking. Marquette, who until then had been peaceful and cooperative, pushed her away and moved toward the crowd, cursing and shouting at the officers that they would have to kill him to take him to jail. The patrolmen pursued Marquette and he resisted.

The watching crowd became hostile, and one of the patrolmen radioed for more help. Within minutes, three more highway patrolmen arrived. Minikus and his partner were now struggling with both Frye brothers. Mrs. Frye, now belligerent, jumped on the back of one of the officers and ripped his shirt. In an attempt to subdue Marquette, one officer swung at his shoulder with a night stick, missed, and struck him on the forehead, inflicting a cut. By 7:23 p.m., all three of the Fryes were under arrest, and other California Highway Patrolmen and, for the first time, LAPD officers had arrived in response to the call for help.

Officers on the scene said there were now more than 1,000 persons in the crowd, which had become agitated and violent, throwing rocks and other objects while shouting at the police officers. About 7:25 p.m., the patrol car with the prisoners, and the tow truck pulling the Frye car, left the scene. At 7:31 p.m., the Fryes arrived at a nearby sheriff’s substation. At 7:40 p.m. any officers left at the scene of the arrest had withdrawn from the angry mob that took to stoning cars and threatening police in the area.

Officers on the scene said there were now more than 1,000 persons in the crowd, which had become agitated and violent, throwing rocks and other objects while shouting at the police officers. About 7:25 p.m., the patrol car with the prisoners, and the tow truck pulling the Frye car, left the scene. At 7:31 p.m., the Fryes arrived at a nearby sheriff’s substation. At 7:40 p.m. any officers left at the scene of the arrest had withdrawn from the angry mob that took to stoning cars and threatening police in the area.

The riots were viewed as a reaction to a pattern of police brutality, repression and other racial injustices suffered by black Americans in Los Angeles, including job and housing discrimination. LAPD Police Chief William Parker did nothing to cool the long-simmering tensions that were now building to a boiling point, when he publicly labeling the people he saw involved in the riots as “monkeys in the zoo”.

Overall, an estimated $40 million in damage was caused as almost 1,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed. Most of the physical damage was confined to white-owned businesses that were said to have caused resentment in the neighborhood due to perceived unfairness. Homes were not attacked, although some caught fire due to proximity to other fires.

By the time the riot subsided four days later, 34 people had been killed, 2,032 injured, and 3,952 arrested. It would stand as the most severe riot in Los Angeles history until the Los Angeles riots of 1992.

Stop No. 7: The House Of Eula Love – 11926 Orchard Avenue

Daryl Gates had been LAPD chief for about a year when Eula Love was gunned down by his police officers on January 3, 1979.

Daryl Gates had been LAPD chief for about a year when Eula Love was gunned down by his police officers on January 3, 1979.

Eula Love was a 39-year-old mother living in this neatly kept bungalow on this street of neatly kept bungalows in this proud and quiet neighborhood. Eula Love was a widow. Her husband had died of sickle cell anemia six months earlier, leaving her to raise their three young daughters and make the mortgage payment and other ends meet on $680 a month in social security benefits.

Eula Love’s $69 gas bill had been past due for as long as her husband had been dead, and when a utility worker from the Southern California Gas Company showed up that afternoon to shut it off if she didn’t make a $22.09 payment, she became irrational and abusive. When he made a move toward the meter she picked up a shovel, struck him in the arm and then chased him off the property.

While the gas man was advising his superiors and making an assault complaint to the police Eula Love walked to a nearby market and purchased a money order in the amount of $22.09. Returning with it in her purse, she was verbally abusive toward a second gas company employee that had arrived and who she found sitting in a truck down on the corner. Leaving him she returned to her house only to emerge brandishing an 11 inch-long boning knife, 5 1/2 inches of which were handle.

Next came the cops.

Officers Edward Hopson and Lloyd O’Callahan arrived at 4:15 p.m. in response to a call about a business dispute. They found Eula Love in the front yard still holding the knife. Exiting their patrol car with guns drawn they ordered her to drop the weapon. Enraged, she did not comply. As they moved closer to her she called them homosexuals. Said they’d had sex with their mothers. Told them to kiss her ass. To shoot her. O’Callahan got close enough to Eula Love to knock the knife out of her hand, but not out of her reach. And when she came up with it the two officers spent the next four seconds emptying their six-shot revolvers. Eula Love was struck by eight of the bullets.

Think about that for four seconds, won’t you? Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. From eight of those explosions, Love took bullets in the right foot, lower left leg, three times in the left thigh, left upper arm, right thigh, and once in the chest. She might have survived those first seven, but the last one took that option away. She died on the grass in front of her home. Two of her daughters inside.

The L.A. County District Attorney’s office, in its report that included the testimony of 52 witnesses, concluded that what officers Hopson and O’Callahan did to Eula Love was not criminal.

Chief Gates’ behavior in the immediate aftermath, however, verged on it.

“I think they had every right and opportunity and justification to do what they did,†he said of Hopson and O’Callahan.

In the parlance, Eula Love’s death was soon departmentally ruled a “good shoot.†There was no mistake in judgment, no violation of LAPD policy, and an entirely unapologetic and seemingly unfeeling Gates relished the opportunity to go on the offensive in deflecting any shame or blame from the officers or his department.

“She decided to solve her problem with a knife,†Gates said. “That’s why it happened.â€

Later on in a speech to the County Bar Association broadcast on local television he chided the press for “wringing every single drop, every tear†from the Love story. Sarcastically he referred to Love as “the poor widow trying to keep her house and home together.â€

It wasn’t $22 she owed, Gates insisted, “it was a $64 or $67 gas bill that had been delinquent for six months!†As if such a negligible difference in amounts could somehow makes her death acceptable.

Never.

Even as an entirely self-involved Hollywood pubescent, news of Love’s death permeated my limited consciousness — and more importantly Gates’ absolute disregard — even contempt — for her life. I don’t mean to excuse Eula Love’s actions. Had she put down the knife and complied with the officers’ commands her daughters still would’ve had their mother. But Gates showed me right then that he wasn’t a chief of police but a general of an army in wartime with little concern for civilian casualties. Eula Love was entirely acceptable as collateral damage. No doubt his support of his officers inspired intense loyalty from many of those he commanded, and maybe he gave us the law enforcement leadership Los Angeles deserved, but I never forgave him for showing anything but arrogance and insensitivity in the wake of such a horror.

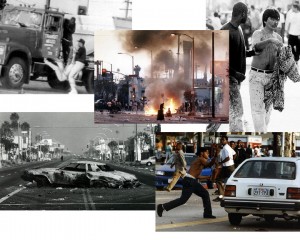

Stop No. 8: 1992 Riots Flashpoint – Florence Avenue & Normandie Avenue

The 1992 Los Angeles Riots, also known as the 1992 Los Angeles Civil Unrest, were sparked on April 29, when a jury acquitted four Los Angeles Police Department officers accused in the videotaped beating of African-American motorist Rodney King following a high-speed pursuit. Thousands of people in the Los Angeles area rioted over the six days following the verdict. Widespread looting, assault, arson and murder occurred, and property damages topped roughly $1 billion. In all, 53 people died during the riots and thousands more were injured.

The 1992 Los Angeles Riots, also known as the 1992 Los Angeles Civil Unrest, were sparked on April 29, when a jury acquitted four Los Angeles Police Department officers accused in the videotaped beating of African-American motorist Rodney King following a high-speed pursuit. Thousands of people in the Los Angeles area rioted over the six days following the verdict. Widespread looting, assault, arson and murder occurred, and property damages topped roughly $1 billion. In all, 53 people died during the riots and thousands more were injured.

The acquittals of the four accused Los Angeles Police Department officers came at 3:15 p.m. local time. By 3:45, a crowd of more than 300 people had appeared at the Los Angeles County Courthouse, most protesting the verdicts passed down a half an hour earlier and many miles away. Between 5 and 6 p.m., a group of two dozen officers, commanded by LAPD Lt. Michael Moulin, confronted a growing African-American crowd at the intersection of Florence and Normandie in South Central Los Angeles. Outnumbered, these officers retreated.[22]Â A new group of protesters appeared at Parker Center, the LAPD’s headquarters, by about 6:30 p.m., and 15 minutes later, the crowd at Florence and Normandie had started looting, attacking vehicles and people, mainly whites.

At approximately 6:45 p.m., Reginald Oliver Denny, a white truck driver who stopped at a traffic light at the intersection of Florence and South Normandie Avenues, was dragged from his vehicle and severely beaten by a mob of local black residents as news helicopters hovered above, recording every blow, including a concrete fragment connecting with Denny’s temple and a cinder block thrown at his head as he lay unconscious in the street. The police never appeared, having been ordered to withdraw for their own safety, although several assailants (the so-called L.A. Four) were later arrested and one, Damian Williams, was sent to prison. Instead, Denny was rescued by an unarmed, African American civilian named Bobby Green Jr. who, seeing the assault live on television, rushed to the scene and drove Denny to the hospital using the victim’s own truck, which carried twenty-seven tons of sand. Denny had to undergo years of rehabilitative therapy, and his speech and ability to walk were permanently damaged. Although several other motorists were brutally beaten by the same mob, Denny remains the best-known victim of the riots because of the live television coverage.

At the same intersection, just minutes after Denny was rescued, another beating was captured on video tape. Fidel Lopez, a self-employed construction worker and Guatemalan immigrant, was ripped from his truck and robbed of nearly $2,000. Damian Williams smashed his forehead open with a car stereo as another rioter attempted to slice his ear off. After Lopez lost consciousness, the crowd spray painted his chest, torso and genitals black.[ Rev. Bennie Newton, an African-American minister who ran an inner-city ministry for troubled youth, prevented others from beating Lopez by placing himself between Lopez and his attackers and shouting “Kill him and you have to kill me, too”. He was also instrumental in helping Lopez get medical aid by taking him to the hospital. Lopez survived the attack, undergoing extensive surgery to reattach his partially severed ear, and months of recovery.

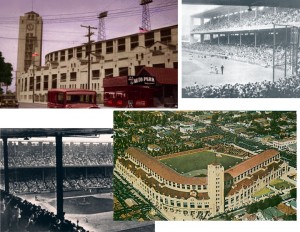

Stop No. 9: Wrigley Field – 42nd Place & Avalon Boulevard

Wrigley Field was built in South Los Angeles in 1925 and was named after William Wrigley Jr., the chewing gum magnate who in addition to owning the Chicago Cubs owned the original Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. In 1925, Wrigley moved the Angels from their home at Washington Park (located at 8th and Hill street)s to this new stadium he had built. Wrigley reportedly built this new stadium and vacated Washington Park when a request to build a parking garage beneath it was rebuffed. Washington Park was demolished in the mid 1950s.

Wrigley Field was built in South Los Angeles in 1925 and was named after William Wrigley Jr., the chewing gum magnate who in addition to owning the Chicago Cubs owned the original Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. In 1925, Wrigley moved the Angels from their home at Washington Park (located at 8th and Hill street)s to this new stadium he had built. Wrigley reportedly built this new stadium and vacated Washington Park when a request to build a parking garage beneath it was rebuffed. Washington Park was demolished in the mid 1950s.

The stadium Wrigley built here resembled a scaled-down version of the Chicago ballpark (known then as Cubs Park) as it looked at the time. The LA stadium was the first of the two ballparks to bear Wrigley’s name, with the Chicago park being named for Wrigley more than a year after the L.A. park’s opening.

Being so ridiculously wealthy, Wrigley also owned Santa Catalina Island, which happened to be where the Cubs held their spring training in that island’s city of Avalon. Probably not coincidentally it is Avalon Boulevard that bordered this Wrigley Field’s eastern side.

The Pacific Coast League prior to 1958 was major league in nearly all respects. With balmy weather that allowed a 200-game schedule, home grown stars like Joe DiMaggio who played for the San Francisco Seals and Ted Williams who played for the San Diego Padres (both of whom no doubt brought their talents and skills to bear in repeated visits to Wrigley Field), and colorful characters like Lefty O’Doul and Casey Stengel, it is unique in the annals of baseball history. With the nearest major league franchise in St. Louis, MO, and only 10 US cities hosting major league ball, the Pacific Coast League created a distinct baseball culture.and was on track to be officially certified as “major” until 1958, when the Dodgers and Giants moved West and took over the league’s top two markets.

In 1926 a year after the Angels inaugurated their new home, the Hollywood Stars were looking for a place to play and found it at Wrigley Field. The Stars began to share the stadium with the Angels during the 1926 season, but it was something of a rugged relationship. After years of disagreements with Wrigley, the Stars moved in the mid-1930s to San Diego to become the Padres, while the Angels continued to flourish here at Wrigley.

The Hollywood Stars would return in 1938, but this was a different franchise altogether then the one that had moved to San Diego. They would only play the one season at Wrigley before moving to Gilmore Field built just for them near Fairfax and Third Street. The Angels meanwhile would continue to play here at Wrigley Field until 1956. So successful was the franchise they were dubbed “The Yankees of the West.”

In 1957 Wrigley Field was sold to the Brooklyn Dodgers in preparation for their move. This forced the Angels to leave Los Angeles and move to Spokane in 1958. The Hollywood Stars also had to vacate their home, since they were also in the territorial area of the Dodgers, and move to Salt Lake City.

In 1958 the Brooklyn Dodgers moved here and became the Los Angeles Dodgers but they rejected the 20,000-seat capacity of Wrigley Field for a ballfield rather awkwardly installed in LA Memorial Coliseum. Even though the coliseum had never been intended to host a baseball game, it was intended to hold a lot of spectators, nearly five times as many as Wrigley Field’s 20,000. In fact the LA Coliseum holds the record for the two largest crowds ever at a ballgame, with 93,103 coming to see the Dodgers and Yankees play in May of 1959 (an exhbition game to honor Roy Campanella). More recently at an exhibition game in 2008, in celebration of the teams 5oth anniversary, a crowd of 115,300 watched the Dodgers lose to the Red Sox.

And during the 1959 World Series, they broke the 92,000 mark every night.

In 1961, the Los Angeles Angels became the American League’s newest team. And while the Dodgers ignored their very own Wrigley Field, the Angels didn’t and were back at Wrigley for the 1961 season — this time however as an American League club. That first season in the majors was an exciting one indeed. It seems that while Wrigley was perfect for Triple-A ball, it couldn’t contain Major League hitting. Wrigley’s new LA Angels would set a Major League record for most home runs in a season (248) that would stand for 35 years until the Seatlle Mariners broke it and finished the 1997 season with 264.

In 1962, the Los Angeles Dodgers finally opened their new stadium, and the Angels decided to hook on there rather then break any more homes’ windows beyond Wrigley’s left field fence. The Angels spent four years at Dodger Stadium awaiting the completion of the Big A in Anaheim.

In 1966, the year that the Angels first played ball at their new home, Wrigley Field was demolished.

— • —

Follow

Follow