An offshoot/evolution of my Watts Happening rides has been my discovery/inclusion of the location of Wrigley Field and the history of the city’s true native baseball team: The Los Angeles Angels. I’ve become so enchanted with the club from an historical perspective as one of the most successful Pacific Coast League (PCL) franchises (who also played their first major league season there; followed by the next four at Dodger Stadium before moving permanently to Orange County) that I’ve gone a little crazy (don’t judge) over at Ebbets Field Flannels buying replica uniform memorabilia (a Wrigley Field groundskeeper jacket, a 1957Â “Los Angeles Baseball Club” tee, and a 1935 home jersey. On top of that I joined the Pacific Coast League Historical Society — and most importantly have switched from a dismissive disdain to an entire embrace of the team’s seriously scoffed-at official name that owner Arte Moreno changed a few years back: The Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim.

Many angelenos — myself included — openly mocked the new title as nothing but a marketing ploy to capture the L.A. audience — and I have no doubt that was part of it. The city of Anaheim even sued to block the switch, unsuccessfully and understandably. But now I also recognize that in my native city whose history is one overly populated with examples of a wanton disregard and destruction of its history, Moreno has boldly anchored a line to our past and rightfully secured the team to the place where it played its first games some 107 years ago.

Many angelenos — myself included — openly mocked the new title as nothing but a marketing ploy to capture the L.A. audience — and I have no doubt that was part of it. The city of Anaheim even sued to block the switch, unsuccessfully and understandably. But now I also recognize that in my native city whose history is one overly populated with examples of a wanton disregard and destruction of its history, Moreno has boldly anchored a line to our past and rightfully secured the team to the place where it played its first games some 107 years ago.

From 1903 through 1925, the team played at the long-gone 15,000-seat Washington Park, at Hill and 8th Streets in downtown Los Angeles. Owner William Wrigley then built Wrigley Field as their home beginning in 1925 and it stood until 1966 (some accounts have it torn down in 1968). On three occasions of my Watts Happening rides I’ve visited the location, each time having discovered and shared a bit more info with the people accompanying me. My most recent one, this past May, spoke of the facts that among the many Angel greats along with those throughout the PCL two of the Greatest To Ever Play The Game — Joe DiMaggio then of the San Francisco Seals and Ted Williams of the San Diego Padres — no doubt played at Wrigley Field; DiMaggio in 1933 (the year of his PCL-record 61-game hitting streak), and Williams in his sophomore season with the club 1937, his hitting helped his team to the pennant that year.

So what? Well, if you’re asking that I can’t blame you. It was a long time ago in a place that no longer exists, in a sport you may not be as interested in as I am. But consider the legendary stature of those two, and perhaps you can realize the impact this local angle has on me. For me, it was something akin to discovering something previously thought impossible, like Michelangelo having painted in London. See, DiMaggio’s and Williams’ amazing careers were forged far away from here, in New York and Boston. From a baseball fan’s perspective that was the other side of the world really what with the closest Major League Baseball team at that time being in St. Louis. So to suddenly learn they specifically took to our Wrigley Field — that they caught and threw and swung and ran its base paths, that they spat and swore and stole and slid — brings these mythological figures not down to earth, but down to my corner of it. These are two of baseballs most glorious gods and they played here. They. Played. Here.

Or rather, they played at what once was here.

Can you imagine having been at one of those games and bearing witness to what was to become such future greatness? Damn. Pardon the digression, but the closest I’ve ever come to doing that was in the early 1990s at the Forum in Inglewood for a tennis match. Before the main event started, two little girls no taller than the net took to the court to play a few games. I’ve long since forgotten the names of the established pro players we’d come to see exhibit their skills, but I’ll never forget the names of those unknowns who wowed the crowd: Venus and Serena Williams.

Anyone still alive who can say they saw “Joltin’ Joe” or “Teddy Ballgame” when… well, that’s almost as ephemeral a thing as the place where they were seen. After the Angels debut major league season ended in 1961, stately Wrigley Field under its signature 12-story clocktower never hosted another baseball game, and five years later in disrepair was demolished.

It’s some consolation at least that the block upon which the stadium once stood now serves the community rather than the for-profit needs of some subdividing residential developer. But it’s sadly typical that what was built there was done with little consideration for what once was and as far as I know there’s nothing to memorialize the ballpark that served a larger community so ably for so long. No sign. No marker. No commemorative plaque sits where once sat home plate to which DiMaggio and Williams and so many others strode.

And that got me thinking: Where might that base be in relation to the place today?

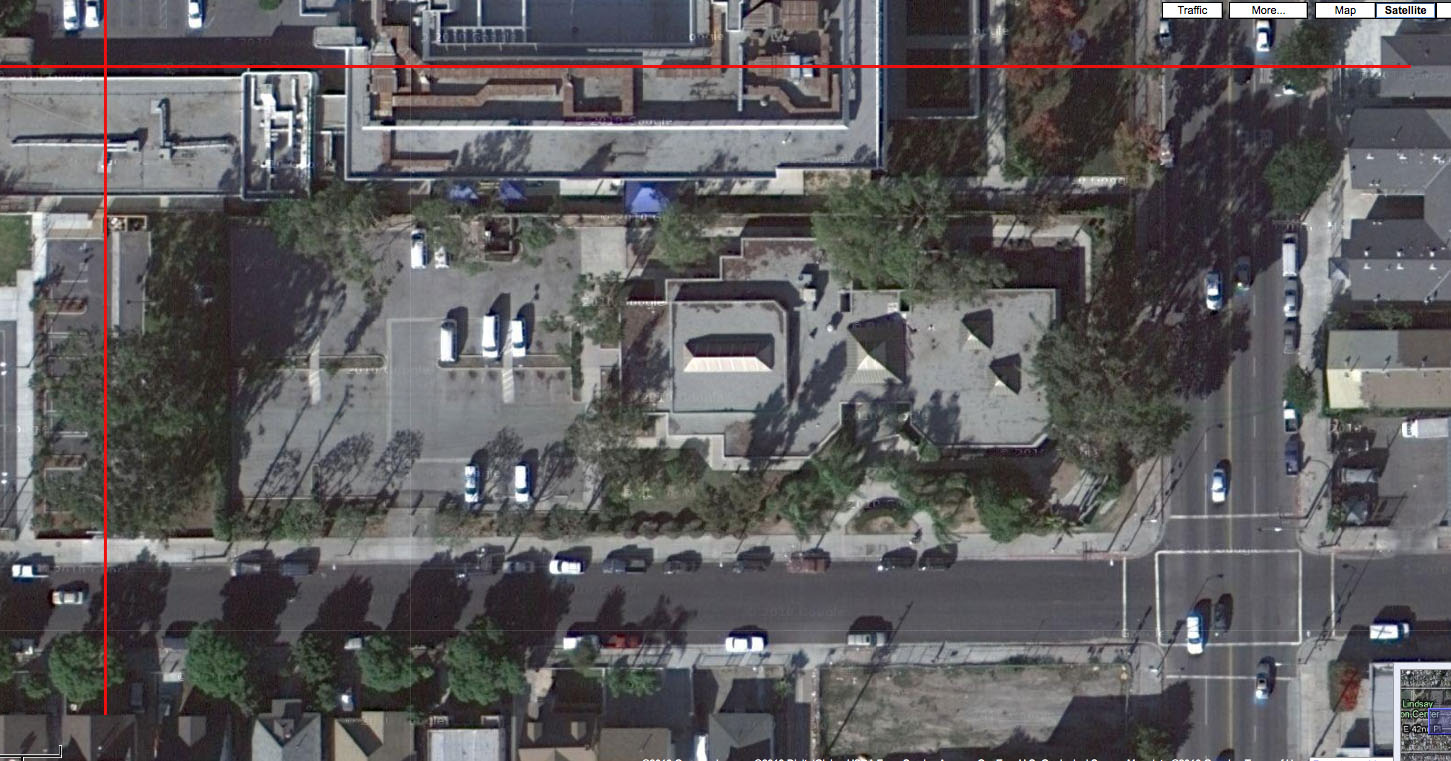

Looking at the satellite image of the block in Google Maps (bordered by 41st and 42nd places to the north and south, and San Pedro and Avalon to the west and east), then comparing it to images I’d found of the ballpark, the location of home plate looked to be beneath a building that’s part of a community mental health center complex standing centrally located.

I then did some entirely unscientific pinpointing on the Google Maps image using neighboring buildings as rough coordinates and at first I was heartened that the intersecting lines (seen in the upper left of image below) seemed to place the base just north of one of the building’s walls.

To verify that I remembered the awesome Historic Aerials website and sure enough I found an image of the block from 1948 (pictured at left). But then when compared to an image on the site from 2005, indeed and sadly, home plate is underneath the structure south of my original intersection, practically equidistant between the building’s north and south facades. Darn it.

There is good news though. Drawing a diagonal line 60 feet and six inches to the north and east of home plate, shows that one can still stand outdoors where Wrigley Field’s pitcher’s mound once stood, albeit now it’s under however much parking lot pavement. Better that than a building.

You can bet on my next Watts Happening Ride, that’s where we’ll be.

Follow

Follow